History

2 May 1958

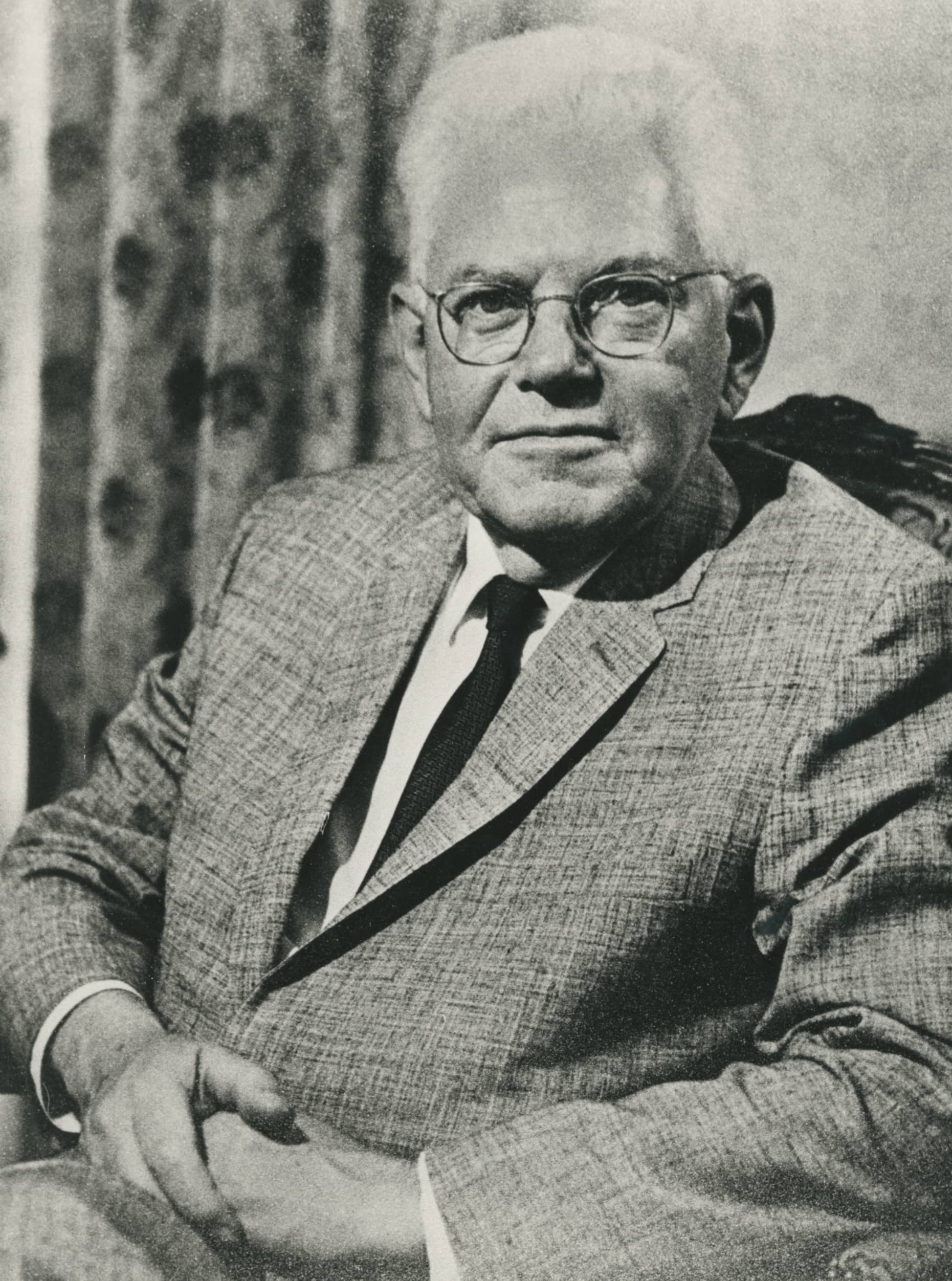

Professor Sir John Eccles

The Right Honourable Prime Minister, Your Excellencies, ladies and gentlemen. It is my pleasant task this afternoon to preside on the occasion of the laying of the foundation stone of the Academy building. I would specially like to welcome our distinguished representatives on the platform, the Prime Minister, Mr Makin representing the leader of the Opposition, Professor Gaddum officially representing the Royal Society of London.

I am going to speak briefly on the Academy itself. It is remarkable that the whole history of the Academy has occurred in Canberra. In 1951 a meeting of leading scientists, technologists and industrialists was held in Canberra to discuss the future of science and technology in Australia. This conference clearly established that there was an urgent need for the establishment, at the highest level, of a national organisation of scientists. The Royal Society of London had long played this important role in Great Britain, having there a position of unquestioned authority in all matters pertaining to science and the applications of science. This conference served to enthuse some of the leading scientists of Australia, notably Professor Oliphant and Dr D F Martyn, with the idea of founding a national academy that would do for Australia what the Royal Society was doing for Great Britain. Fortunately there were resident in Australia 11 Fellows of the Royal Society of London and in order to make a sufficiently representative body these Fellows selected a further 13 scientists to help in the task of founding the Australian Academy of Science, as it was to be called. In July 1952 there was a memorable meeting with the Australian National Research Council here in Canberra and the Officers of this Council, under the Chairmanship of Professor Elkin, with great magnanimity, agreed to recommend to their members that the Australian National Research Council be dissolved in order to make way for the Australian Academy of Science, provided that the new Academy assumed responsibility for the various duties and functions of the ANRC. The stage was thus set for forming the Academy of Science and petitioning for a Royal Charter. A council of 10 was set up with Professor Oliphant as the first President.

In response to representation to the Prime Minister an annual grant of £10,000 was made to the Academy and the Prime Minister also facilitated the negotiation in respect of the Royal Charter, but the Academy will always be especially grateful for the historic occasion on February 16th 1954 when her Majesty, Queen Elizabeth II founded the Australian Academy of Science in a private ceremony attended by the President of the Academy and members of the Council. The historic character of this occasion will be appreciated when I inform you that this is the second occasion on which a reigning British Monarch has personally founded a scientific academy. The first occasion was almost 300 years earlier when Charles II founded the Royal Society of London.

After the founding ceremony the infant Academy set upon a vigorous policy of development in order to fit it for its self-appointed task of developing and applying science in Australia. Undoubtedly the first concern of the early Academy was to ensure its growth and development by election of Fellows having the highest level of scientific and technological attainment and also of Fellows who have rendered conspicuous service to science and the application of science. But already the Academy has an impressive record of achievement. Firstly, I would mention that it has caused the scientific community of Australia to know itself so that there is more friendly cooperation and understanding and less antipathy.

Secondly, I venture to think that the possibility of election to the Academy provides an incentive to young scientists. We are all human and I believe greatly in incentives at all levels.

Thirdly, the Academy has represented Australia internationally on many occasions. Our greatest task in this respect has been the International Geophysical Year where we have been entrusted with a major share of Australia’s efforts in a spectacular and worldwide project. During the last year we have also been responsible for Australia’s representation at the Pacific Science Congress and the Pan Indian Ocean Conference. At present we are making plans to have international conferences in Australia in specially appropriate fields. Thus Australia is rightfully taking its place at a high level in the fields of scientific endeavour.

Fourthly, the Academy has been vitally concerned in the application of science to many local problems of great practical value to Australia—scientific manpower, water resources, the Kosciusko Tops and erosion problem, man and animals in the tropics, oceanography and so on over a wide field of applied science. It has been responsible for meetings and symposia on these important problems, employing to the fullest extent experts in the various fields. Whether Fellows of the Academy or not they have given devoted service.

Well now, that is just an account of what the Academy stands for and what it has done and I now have great pleasure in calling upon Professor Oliphant to tell you something about the building. Professor Oliphant.

Professor Sir Mark Oliphant

Mr President, Mr Prime Minister, Your Excellencies, ladies and gentlemen. An organisation, for whatever purpose it is created, must have a home. The Academy of Science, founded under such auspicious circumstances by her Majesty the Queen, has sought to provide itself with a home, a headquarters for science in Australia. A national home for a national activity as important in the future of this country as is science in Australia, might well be expected in these days to be provided by the Commonwealth Government. However it is well known that men of science are independent folk and often extremely cussed people and the feeling that the Academy should be as separate from the functions of government as possible was reinforced when those two outstanding figures in the development of Australia, Mr W S Robinson and Mr Essington Lewis, were elected to its Fellowship. Encouraged by our first Treasurer, Dr Hedley Marston, Mr W S Robinson was able to persuade (perhaps I should say blackmail) many leaders of industry into the recognition of the fact that they should support the claims of science for a national headquarters and very generous donations were received from the non-ferrous metal industries, from the oil companies and from the motor car manufacturers. Mr.Essington Lewis ensured that a notable contribution came from the steel industry.

Meanwhile Dr Marston and I had approached other industries and we found the same generous response from the paper manufacturers, the glass manufacturers, the trading banks and many others. We are very happy to have with us today representatives of several of our major benefactors. Recently we received our first donation from the primary industries of Australia which have probably benefited so much from the application of scientific knowledge to their many problems; indeed, benefited more perhaps than any other section of Australian industry. Australian Estates Pty Ltd, a Company with its headquarters in London, by the way, has made a donation of £1,000. We hope that further support will come from those primary industries which are the backbone of Australia. At the present time we have received a total of £115,000, towards a goal of £250,000.

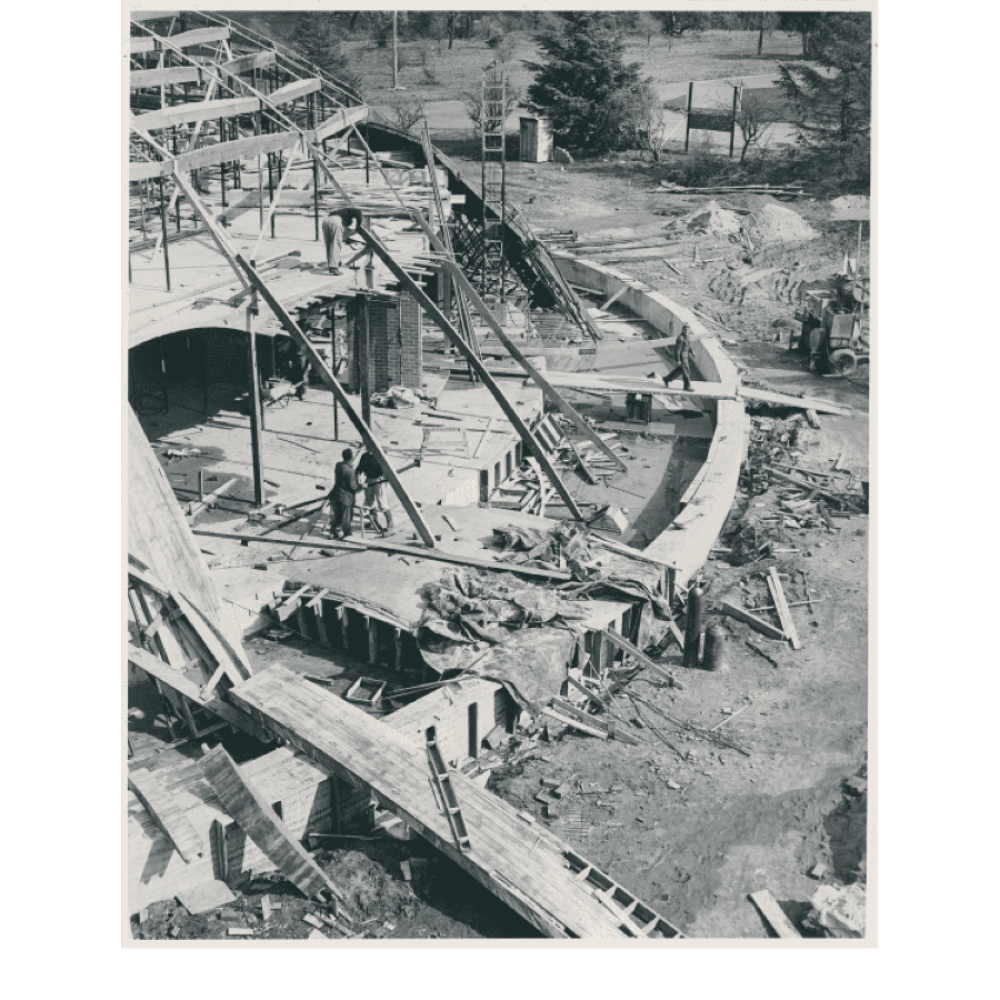

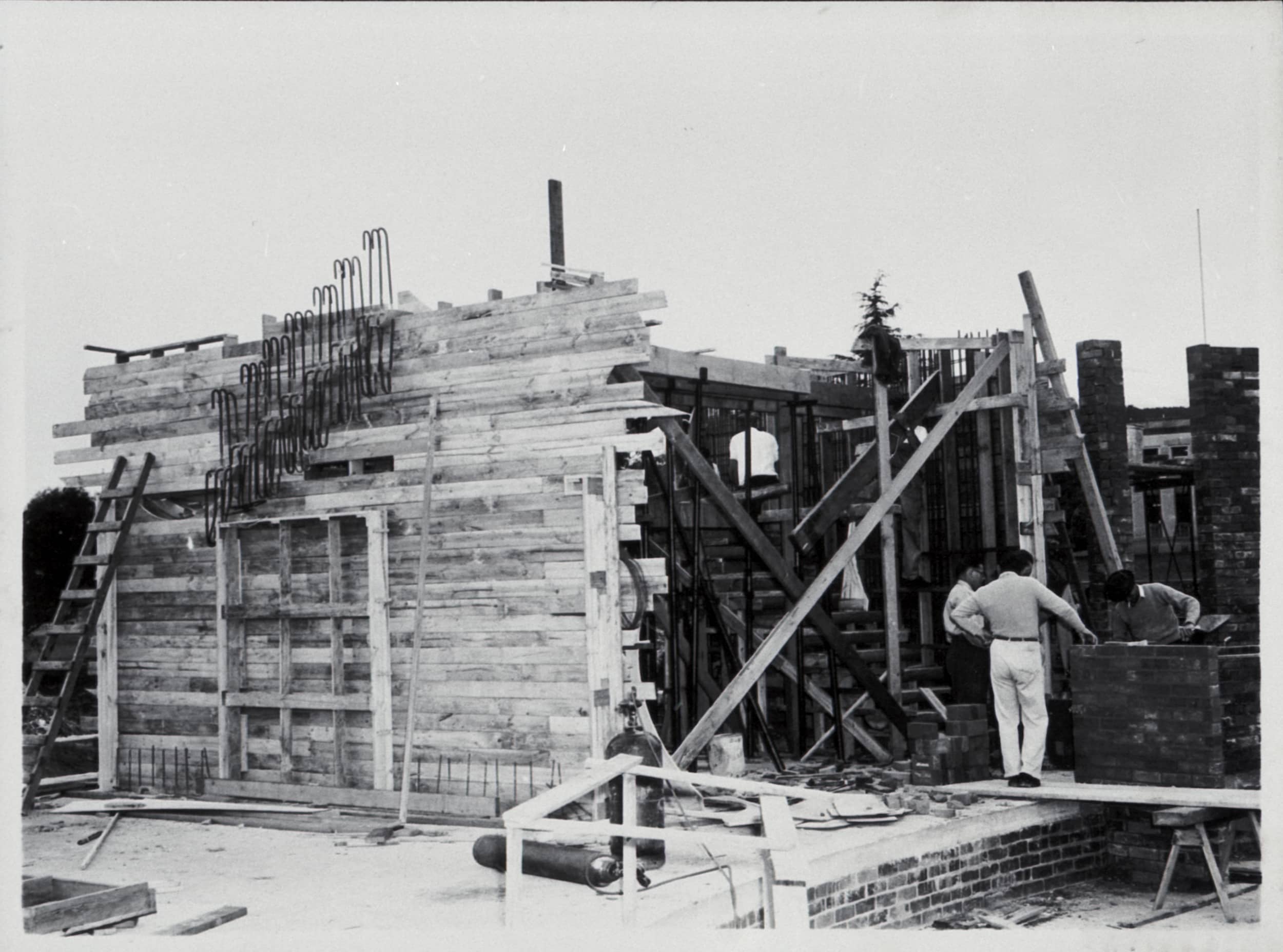

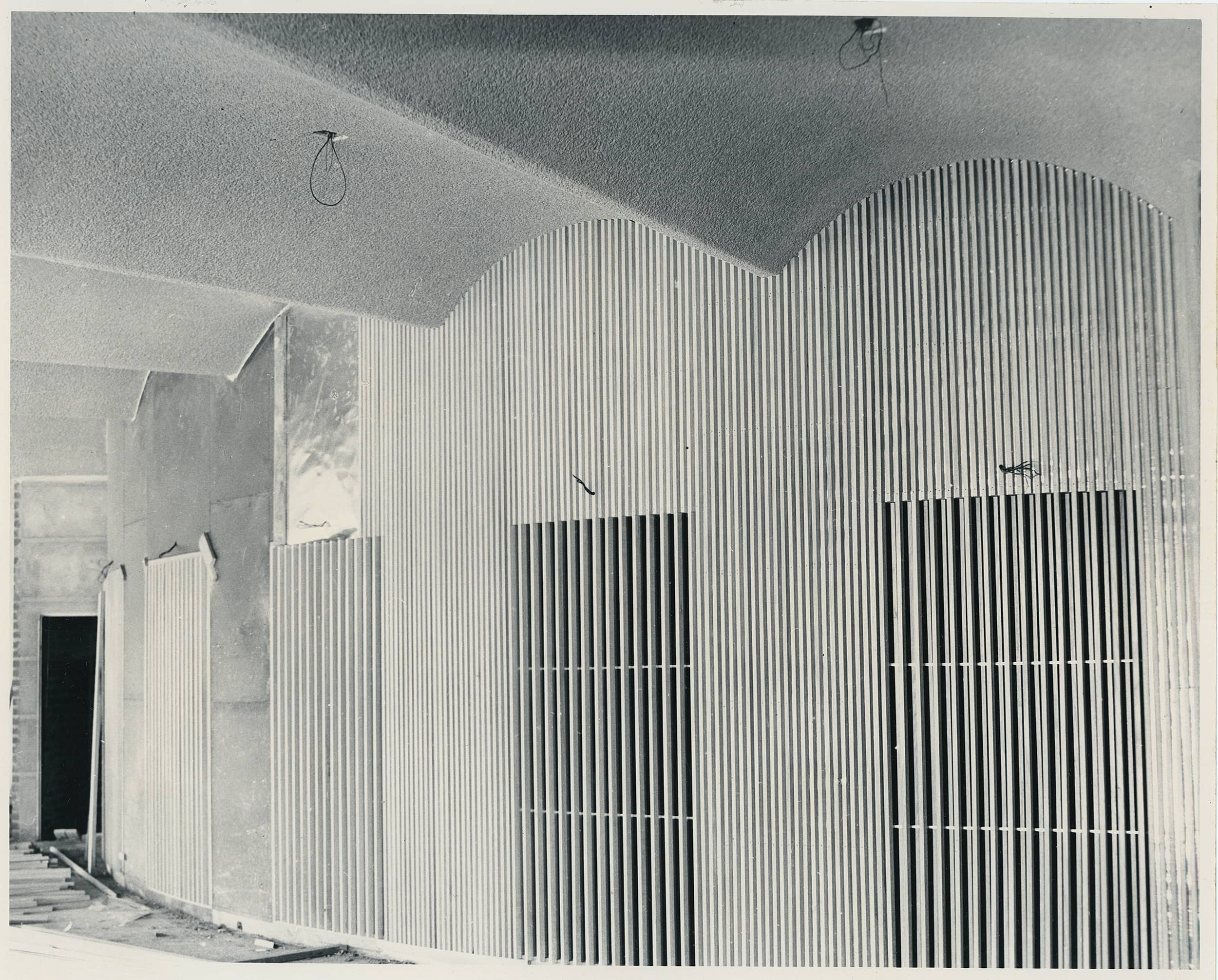

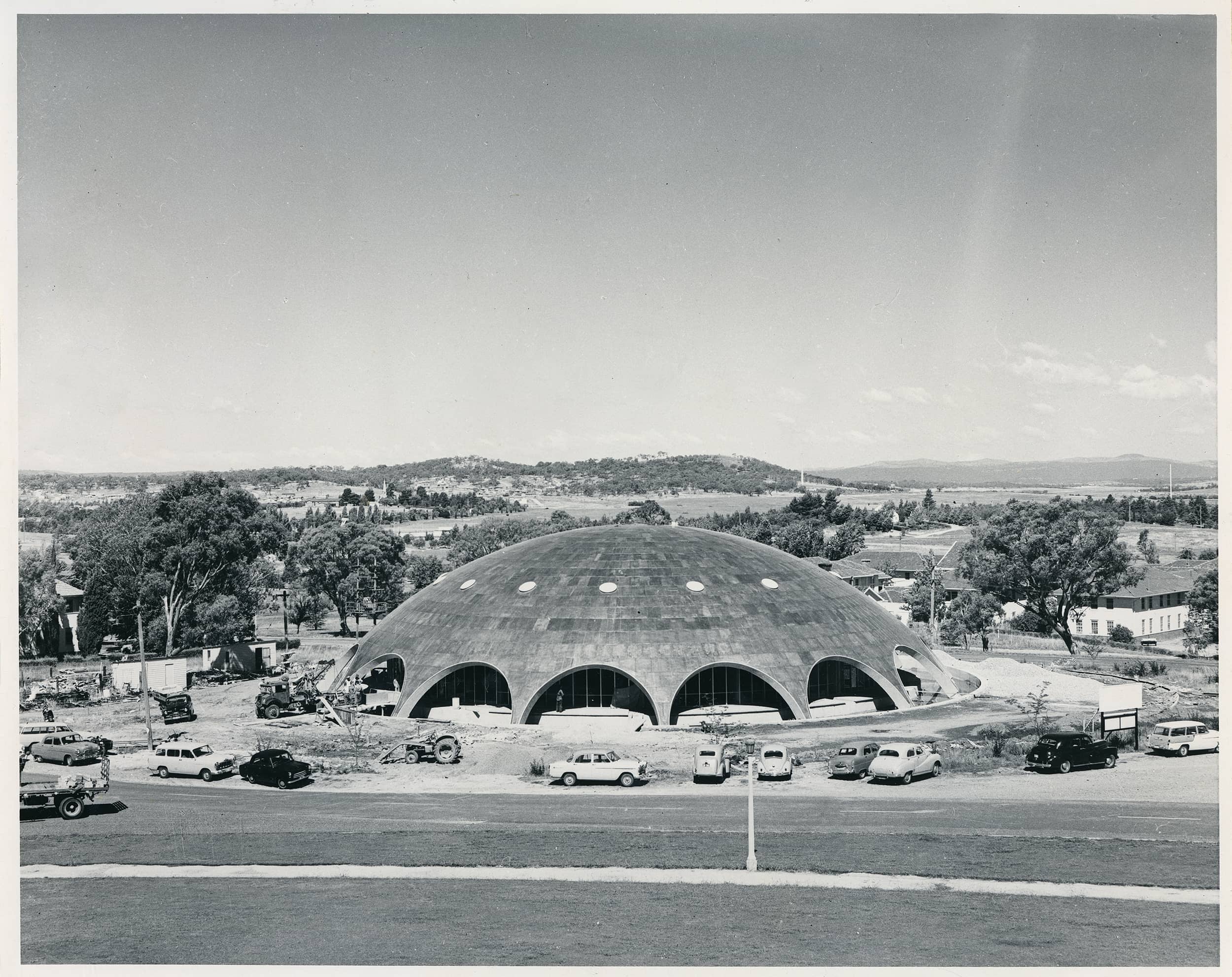

Nevertheless, the Academy has had sufficient faith in the public appreciation of the outstanding significance of science in Australia to decide to go ahead with its building program. It has sought to provide a fitting, but modest headquarters which will symbolise the meaning of science and the spirit of the search for natural knowledge. In this task we have been aided enormously by the architect, who we were lucky enough, perhaps I should say wise enough, to choose to design the building. The Department of the Interior made available to us this magnificent site with its semi-circular frontage to the Institute of Anatomy and adjacent to the National University and to Canberra University College. Mr Roy Grounds, of Grounds, Romberg and Boyd, with remarkable insight into our needs and with the boldness of the true contemporary artist, has designed a building which we believe will prove to be one of the great creations of this period of architecture. The round conference room, which is behind those seated here, to seat about 250 persons under proper conditions for serious discussion of scientific and technical matters, is the core of this building. Offices and reception rooms are arranged around it under a dome of copper-clad shell concrete. The whole will be surrounded by a cloister and a decorative moat and the grounds will be suitably landscaped. The Academy has been fortunate too, to have as the contractors for its building so experienced, so well equipped and so skilful a firm as Civil and Civic Contractors Ltd. The work which they have done to date is good and we are sure that the completed building, which should be finished in about one year from now, will be a credit to the architects, the builders and we hope a very suitable home for science in Australia.

I call upon the Prime Minister, having laid the stone now to briefly address us. The Prime Minister.

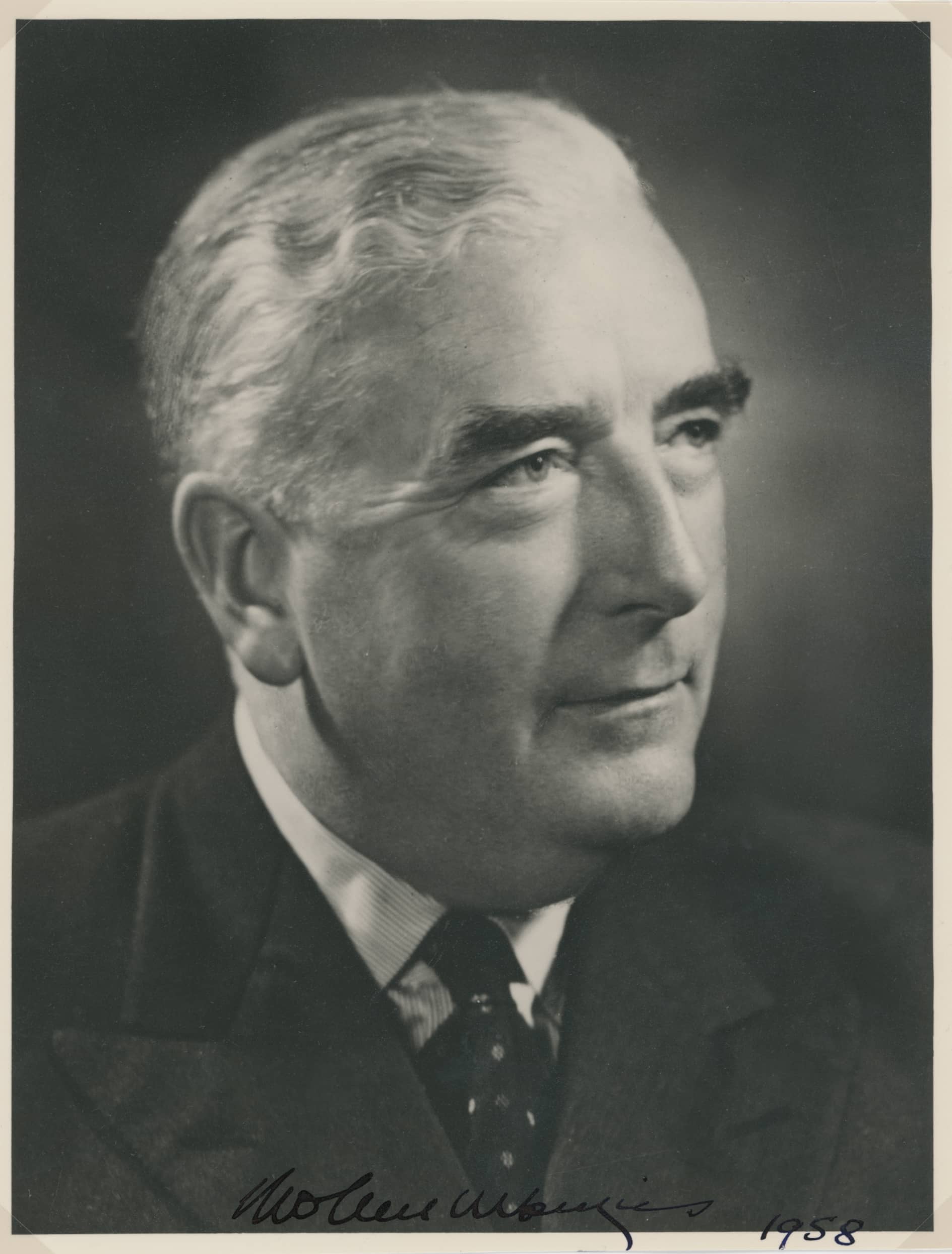

Robert Menzies - Prime Minister

Sir, Mr Makin, Your Excellencies, and ladies and gentlemen. I was about to utter the mystic words “I declare this stone well and truly laid”, but come to think of it, I think it is a little bit off true. Anyhow, now doubt I am wrong and this is off true. I think perhaps I ought to tell you that I have been enriched with some information about this stone. This is like me, it comes from Melbourne and has been planted now here and it is one of the old piers of the Melbourne Observatory, dating back to 1870. I was very kindly forwarded with the history of it, which I read with immense pleasure, particularly when I discovered that at the time when they were discussing establishing an Observatory in Melbourne and this stone became one of the piers supporting it, the Committee in Melbourne, it’s to be admitted, recommended that the Observatory ought to be established in that City, not only because of its geographical position, but because of the clearness of the air; a quality about Melbourne that I have always asserted but which I find constantly denied by those people unfortunate enough to be born in other places. And here it is, a souvenir, a very impressive souvenir of that Observatory in Melbourne, the old Observatory, the foundations of which run back really to the initial discussions in about 1852 and I like that, sir, if I may say so, because it’s a very good thing, indeed it’s one of the things aimed at by this Academy, that we should not fall into the error of thinking that science began this morning. We’re a little bit tempted to think that way in many aspects of life, you know ‘Here today, gone tomorrow. Everything that we know is quite new, everything that was known before was irrelevant’. It’s a very good thing to be reminded occasionally that we’re not only the creators of some things, but we’re the inheritors of a great number more and therefore there is a tradition in science, there is a body of knowledge in science of which these distinguished men who belong to the Australian Academy are at once the inheritors and the expositors and to which they themselves undoubtedly are adding material volumes of knowledge.

And so continuity, as in many other things, indeed as in all other things, is of the essence and therefore, sir, I rather like the idea that this stone, simply inscribed then placed in that form, is something that serves as a nexus between this most modern of buildings, as it will be in an older day when buildings of this kind were perhaps never thought of.

One other thing, or perhaps two other things, I would like to say because I don’t want to make a long speech to you. I am very proud of having had some association with the formation of this Academy. It’s quite true that on each occasion of the two on which I was brought into it I was the victim of the persuasive faculties of Professor Eccles and the downright capacity for, well, what shall I say, of Professor Oliphant. They came to see me in the first place, they expounded their views about an Academy of Science and we had a very fascinating and, of course, highly intellectual discussion about it and then I gave them some advice, very good advice I thought, anyhow, in a broad way they acted on it, I waited, waited for the blow to strike. You know, waited for Oliphant to say ‘That will cost you so many thousand pounds’ but with the skill that he is rapidly acquiring in this city, he said nothing that day. That was indoctrination day. That was ‘getting me interested’ day and then of course, the moment I committed myself to say ‘Well, now look, I don’t mind giving you some advice as to how about getting a Royal Charter and all that kind of thing and a few notions about the rules that have to be observed’. It was only the next morning when I woke up and looked back and knew that I was lost. And, of course, it was quite right because a fortnight later Oliphant, with the most ingratiating style, came along to me and in the homely phrase ‘Nipped me’ and then ever since then I have remained ‘nipped’, but very proud I am to have been nipped because I think that the day will come when in Australia those who were associated, and there are some very famous men have been referred to here this afternoon, those who have been associated with the establishment of this Academy will be greatly envied by those who, at that time, will realise what great work this body has done.

Its task is not easy—perhaps you will allow me to add this before I conclude—its task is not easy, it must be completely selective in its membership because it’s of the essence that its standards should be high. There was never a time when high standards were more needed than in a world in which, as has been truly said, there is the constant danger of the mass mentality created by mass means, either of instruction or of entertainment and therefore the standards must be high, they must be selective and yet at the same time they are not to be narrow, they are not to be conservative, they are not to exclude from consideration people who have something good to do for the future of science. We are all tempted when we get to my age to become a little defensive about our own ideas about our own particular knowledge, about our own particular skills, whatever they may be. That is to be guarded against because if there’s one thing that shines out in the history of this century it is the enormous capacity of science to expand its boundaries. The degree to which matters of the greatest complexity have been evolved and built on in our own lifetime is not only fascinating, but positively bewildering and he would be a very dull soul, I think, who didn’t realise that by the end of this century, when most of us will not be here as first-hand witnesses, but will have, I trust, a good view from on high, by the end of this century it is quite clear that the boundaries of knowledge to the activities of scientists will have been pushed back to places as yet unseen and unimagined and in all that in our own country this Academy, established by the finest body of scientists this country has ever had, adding as it will in the future to its own numbers men of corresponding faculty, men and women of corresponding gifts and enthusiasm, is going to make a contribution to the body of scientific knowledge in the world, which won’t be just confined to Canberra, but will extend over the world. Indeed, sir, let us all remember, as temporary or permanent residents of this small city, that there is a temptation in Australia to think of Canberra as something remote, as something detached, as something unaffected by the pulse of the life of the nation. The more we do of this kind, the more will that fallacy disappear, the more will it be understood that this is not merely the Capital of Australia by Act of Parliament, but is the centre of Australia in many of the great intellectual activities in which the people of Australia will have to engage.

Sir, I declare the stone well and truly laid.

Professor Sir John Eccles

I think we have all listened to a most remarkable and memorable speech by our Prime Minster, for which, on behalf of the Academy, I thank him very much. I also thank him for officiating on this ceremonial occasion on a stone which has had a long history and which is at last, we hope, permanently resting here as an historic exhibit of the early days of Australia, bringing, as he said, memories of the past up to the present. I now declare this occasion at an end. Thank you very much.

6 May 1959

Professor Sir John Eccles

Your Excellency, Excellencies, Mr Deputy Prime Minister, Members of the Government, Your Grace, My Lord Bishop, ladies and gentlemen. I welcome you to our home. We are assembled on a great occasion in the life of the Australian Academy of Science. His Excellency, Sir William Slim, has graciously consented to be present and formally to declare this building open. As yet, the Academy is very young. It is just over five years since Her Majesty, Queen Elizabeth, presented her Charter in person to the Provisional Council of the Academy at Government House in Canberra and already, as if by the magic that recalls to us the Arabian Nights, this fine home of the Academy has arisen in its perfection of form and is to be opened complete in every detail. Tomorrow it will be used for the first time for an official function, the fifth Annual General Meeting of the Academy.

But it is not for me to tell you about the building. This task I leave to Sir Mark Oliphant and it is appropriate that I do so for two reasons—as the first President of the Academy and the Chairman of the Building Committee he has played an all important role in every step that has led to the ceremony of today. My other reason is in a lighter vein. The public is very ready to believe that nuclear physicists are magicians and this building does look like a home for magicians, not only in the amazing way it has grown but also in its unique style. My task, as a biological scientist is to tell you something of the life history of the Academy, our conception, birth and growth and also what we do and how we hope to develop in the future. As with all industrially advanced countries Australia is increasingly dependent on science and technology for the development of her natural resources, for the efficiency of her industries, for the well-being and protection of her people. Only by the continued effort to use to the full the intellectual and technical potentialities of her people can any country achieve and maintain a place in the forefront of civilisation in this most progressive of centuries. Material resources in themselves are of secondary importance, as is witnessed by the amazing performance of countries such as Denmark and Holland. Within limits material deficiencies may even contribute to the scientific and technological advancement of a country for deficiencies provide an especial challenge. In Australia we have several such challenges—the widespread aridity, the oil impoverishment, the trace metal deficiencies in our soil.

The need for a national scientific body of the highest standing led in 1919 to the formation of the Australian National Research Council and thanks to the devoted efforts of its leaders the ANRC gave most valuable service to Australia, yet it would be generally agreed that it had failed to achieve the status that was required of a national body with such weighty responsibilities. Various efforts and internal reforms of the ANRC proved to be impracticable and a more radical proposal emerged from a Conference on Science in Australia, organised by the Australian National University in 1951. At this Conference and in the subsequent discussions, there was fairly general agreement that an Academy of Science, with much more restricted membership, should replace the ANRC. Eventually the Fellows of the Royal Society of London, resident in Australia, took the initiative in forming the Australian Academy of Science by adding to their number other Australian scientists of equivalent status, then petitioning for a Royal Charter and securing a larger income via Government Grant. Meanwhile the ANRC Executive, with great magnanimity, agreed to its dissolution in order to make way for the new Academy.

This was a fine act of self-sacrifice made in the belief that the new Academy would be better fitted to give leadership in the scientific development of Australia. A memorable Valedictory Dinner of the ANRC was held in Melbourne in 1955 and to give some idea of the goodwill I cannot do better than quote from Professor Cherry’s speech. ‘It is indeed an unparalleled occasion which demands a Miltonic illustration from history and from legend. One thinks, for instance, of the Arabian Phoenix, building with loving care that pile of branches which is to be both its nest and its funeral pyre. For it is to be consumed by fire and it is from the ashes that there arises its young and glorious successor.’ But that analogy is not quite right. The Research Council is to have its consummation not by fire but by dissolution and for solvent there has been chosen a liquid more potent than water—alcohol. Professor Cherry went on to say ‘The essential thing is that we shall succeed if we do such things as earn us the continuing confidence and support of Australian scientists at large. As to that we are resolved to be a working body. We shall succeed if we work with the same devotion, disinterestedness, order and good sense as I have observed from the sidelines for the past twenty years in the ANRC with its Chairmen, McCallum, Ward and Elkin’. Well now, that is the end of Professor Cherry’s remarks on that occasion.

The new Academy chose to model itself closely on the Royal Society of London, so taking advantage of three centuries of wisdom. The Academy is also especially indebted to the Royal Society for help in its petitioning for the Royal Charter and for the gift of a magnificent Signature Book that is a replica of the original Signature Book of the Royal Society and today they have sent as their official Representative, Sir Lindor Brown, the Senior Vice-President and Biological Secretary. We take great pleasure in regarding the Academy as a daughter institution. From the very beginning it has been of prime importance to ensure that the highest standards were maintained in the election to the Fellowship and that it was truly representative of all aspects of pure and applied science. It could be claimed that it has retained the confidence of the general body of scientists in Australia. In another personal way, it has succeeded better than we dared to hope. As a national body with membership drawn from the Universities, the CSIRO and other research institutions it has been instrumental in eliminating the jealous rivalry that had grown up between the Universities and the CSIRO. The affiliation of scientists is not even thought of in electing them to Fellowships or choosing them for positions of responsibility in the Academy. We are concerned solely with the advancement of science in Australia and in the world generally, or to express it more tersely, our concern is with science not with scientists as such. As will be seen in our Year Books, the functions of the Academy are both national and international. At the national level we have certain general responsibilities in the fostering of science and in its publication. I should mention here the biennial Matthew Flinders Lecture, which is the first lecture to be endowed by the Academy. We have organised a Symposium and issued a report on the grave problem of the shortage of scientific manpower and have also provided a special report on science in Universities for the Murray Committee. In part the implementation of the Murray Committee report will alleviate the manpower situation but several important problems remain unsolved and in the national interest the Academy will press for further action. At the national level our special responsibilities are very diverse, like in instance the Koszciusko catchment area, hydrology, tropical climatology, oceanography—nothing seems too large or too localised for we have recently acted in defence of the elephant seals in Macquarie Island.

However, it is at the international level that the Academy has its principal opportunities and functions. Firstly, it is the body representing Australia at all the International Scientific Unions as well as the Pacific Science Congress and the Pan Indian Ocean Congress. Secondly, it undertakes international scientific tasks for Australia. The most notable has been the International Geophysical Year, the Academy being responsible for Australia’s fine contribution. From the I.G.Y. there have developed further important international activities in which again the Academy represents Australia. The Special Committee for Antarctic Research and the Committee for Space Research are of vital interest to Australia and we have achieved a high status in both. The third meeting of the SCAR was held in Canberra this year and was generally agreed to be very successful. Amongst other achievements was the inauguration of the International Antarctic Analysis Centre as an annexe to the Bureau of Meteorology in Melbourne. Other international activities are the organisation of specialist international scientific meetings in Australia. In August a specialist biochemical meeting on Haematin Enzymes will be held in this building. It is a field in which Australia holds a high place and many of the leaders in other countries will come to Australia for the conference. Next year the Academy is arranging for an international conference on the Chemistry of Natural Products that will be held in Melbourne, Sydney and Canberra. These meetings are of great value in putting Australia on the scientific map and exhibiting our very considerable achievements in various fields of science. In all these national and international activities the Academy can count on the devoted service, not only of its own Fellowship, but of other scientists of Australia as well. Our aim is to select the scientists best fitted for these special purposes regardless of their affiliation with the Academy. On the Standing and National Committees of the Academy the Fellows are outnumbered and often scientists, who are not Fellows, hold key positions, for example, the success of Australia’s contribution to the International Geophysical Year has been in large measure due to the Convenor of the National Committee, Professor Hugh Webster. The scientists of Australia regard it as a real honour to be selected as members of our various Committees.

Let us look now into the future. Where do we go from here? I can assure you that there will be no relaxation of our labours now that we have a centre for science in Australia. This centre has fine symbolism with its geometrical form and its great restraint of line and décor. You can well imagine how much it will contribute to the atmosphere of many national and international conferences that will be held here in the forthcoming years. From here the Academy can radiate its influence over Australia and the world and receive from the world for Australia. But every end is a new beginning and the Academy is now planning to become, as well, a channel for benefactions for scientific purposes and so to exert our influence, not only through expert committees, and individually by our Fellows, but also by providing the finance for research projects. Benefactors would be secure in the knowledge that their contributions were being administered by the collective scientific wisdom of the Academy, rather than by the authority of any one scientist, however eminent. So the Academy goes forward into the future like some great caravan of exploration and discovery, always being joined by new recruits, always enlisting the help of other scientists best fitted for any particular project so that we can continue to command the cooperative effort of the scientists of Australia.

I now have much pleasure in calling on Sir Mark Oliphant, the Chairman of the Building Committee. Sir Mark Oliphant.

Sir Mark Oliphant

Mr President, Your Excellency, Mr Deputy Prime Minister and members of Government, Excellencies, Your Grace my Lord Bishop, ladies and gentlemen. An Academy without a home is like a family without a home. Thanks to the National University the Academy has been provided with an office, first in the Research School of Physical Sciences and then in the John Curtin School of Medical Research. However, the first Council and Officers realised very clearly that one of their principal aims must be to find a Headquarters which was not within the National University or any other organisation, if the Academy was to maintain its independence and be able to follow only its chosen path, as set out in its Charter—the advancement of natural knowledge. The first Treasurer, Dr Hedley Marston, and Mr W S Robinson, our Senior Fellow, were the prime movers in the search for funds with which to establish a national headquarters for science in this Federal capital. Their success in persuading some great enterprises that they should support the basic science upon which all industrial advancements rested encouraged others. Mr Essington Lewis, as would be expected of the father of BHP as we know it, added his weight to the appeal. His Excellency, unknowingly, played his part by enabling me to meet Lord Stratharnan at Government House, thereby assuring the support of the oil industry.

When a substantial sum had been received from our generous donors, even though it fell far short of what was required, Council took the bold step of authorising the Building Committee to negotiate for a site and to commission an architect. This fine site was made available by the Department of the Interior. The revolutionary concept of Mr Roy Grounds of Grounds Romberg and Boyd was chosen as most in keeping with the nature and objectives of the Academy of Science. Mr Grounds devoted himself to the task with enormous enthusiasm and imaginative insight and we were able to approve his plans and to let a contract in January 1958. The technical story of the design and erection of the domed building has been told in the booklet which has been distributed. Examples of plans and working drawings have been arranged by Mr Grounds as a display in the gallery on the first floor which you are invited to inspect. You need only to look around you to appreciate how successful this pioneering enterprise has been. My task today is to say how grateful we are to Mr Grounds and his partners and consultants for the inspired design and painstaking supervision throughout. To express our deep admiration for the skilled organisation of the builders, Civil and Civic Contractors Ltd., their Managing Director, Mr Dusseldorf and his assistants. To say how much we appreciate the magnificent craftsmanship of the Canberra tradesmen who did the actual building so rapidly and so well. To thank Mrs Grounds and Mr F Ward for the distinctive furniture and furnishings which grace this chamber and other rooms and to say how grateful we are to Professor Pryor and to the Department of the Interior for the layout, construction and planting of the surrounding grounds and roads. Above all, I have to offer our warmest thanks to the many generous benefactors who have subscribed to date over one half of the cost of this building. To the Prime Minister, Mr Menzies, who has encouraged and helped the Academy from its birth and to his Government which has adopted us as responsible and even respectable national institution which merits the continuing support of Australia, its industry and its commerce. Finally, I must thank our Assistant Secretary, Mr Deeble, upon whom much of the burden of administration has fallen and all others who have contributed in many ways to the successful completion of a chamber and offices of which we are justly proud.

The Academy of Science now possesses a home and its existence is apparent to all who come to Canberra. It is our pleasure to provide offices and the use of the chamber and its reception rooms for the Humanities Research Council and the Social Sciences Research Council. These sister organisations share many of the aims of the Academy and it is fitting that they shall share in the future, our roof and to leaven with humanity our approach to the problems which confront men of science in this technological age. We hope too, that other bodies of serious aim will use this building, which we believe will become a national asset of increasing value and importance to a developing Australia.

Professor Sir John Eccles

I now have much pleasure in inviting His Excellency to address you and formally to declare this building open.

His Excellency—Field Marshall Sir William Slim

Governor General

Mr President, Mr Acting Prime Minister, Your Excellencies, ladies and gentlemen.

I am delighted to be able to tell you that yesterday I received a message from the Queen with her command that I should convey it to you. Before I address you I will read that message from her Majesty; this is the message – “Please convey my good wishes to all assembled at the opening of the Australian Academy of Science Building on Wednesday. I am confident that the Academy, to which I presented its Charter five years ago, will play a significant part in the acquisition of scientific knowledge and in applying it to the progress and welfare of my subjects in the Commonwealth of Australia—Elizabeth R”.

The President of the Academy, Sir John Eccles, has handed me a reply which I shall be delighted to convey to Her Majesty—“We are honoured and deeply grateful for Your Majesty’s gracious message. We have been inspired by the confidence you have expressed, both when you presented the Charter five years ago and now on the occasion on the opening of our building. We will ever strive to be worthy of your confidence in our efforts to benefit our country and your subjects”.

Mr President, ladies and gentlemen. There is no country anywhere to which science is more important than to Australia. No longer does the Australian march out with his axe on his shoulder to hack out a homestead from the wilderness, yet we are still a pioneering people, still marching out to wrest a better life from our land. But the time has passed for the old pioneering methods of trial and error. We can’t succeed unless we adopt the methods of the new pioneering, the blending of practical experience with the discoveries of science. If I press down a switch here a light will flood on from above, but that’s not merely because I pressed a switch but because over the years a thousand men have each contributed their part to make the light shine. Many of those shares were important, some vital, all necessary to the achievement, but there was one contribution, without which none of the rest would even have been thought of, the original basic discovery on which all that follows is based and that was the work of a scientist - some scientist engaged in research. Without such research none of the modern inventions or amenities that we enjoy would have been possible. Nor, without the continuance of that research will any others in future. It’s sad, therefore, that the amount of research done in Australia is still, on a comparative scale with other advanced countries, small. True, research is awfully expensive and it may not show quick results but in fact there is no investment that will pay so large a dividend in material benefit as money wisely spent on scientific research and we are extremely fortunate in this country that we have so many leaders in our industry and other walks of life who are wise enough to recognise that and public-spirited enough to act upon it. By fostering, planning, guiding and organising this research in Australia this Academy is already and will increasingly make itself, one of the most vital and valuable of our national organisations.

Obviously, if we are to increase the amount of research, both basic and applied that is to be done in the country we shall have to get more scientists. Our own Australian scientists have won world recognition and we now, more and more, attract distinguished scientists from other countries, yet scientific progress here will depend almost entirely on our own recruitment in Australia. As an outside observer, I am not sure we are going the best way to enlist and train our recruit scientists. In science it’s quality rather than quantity that counts, especially if we are to build up in this country a great potential of science. It’s not the number of science students that we have but how many capable and qualified scientists we produce. At the moment we cram our Science Faculties until they burst at the seams, well knowing that a dismaying percentage of the students will never stay the course and then having done that we moan about the lack of accommodation. It seems to me that possibly a quicker way to get the scientists we want, to improve scientific education and at the same time to save a vast waste of time, money and teaching capacity would be to eliminate unsuitable students before entry. With surely the application of a little of the scientific method to the study of this problem we should hope to separate the undoubted goats from the potential sheep.

There are two factors which affect the progress of science and its application in almost all countries, but most severely, I think, here in Australia. At its very beginnings science is hampered by the dearth of science teachers in our secondary schools. It’s indeed in this respect, more I think than in any other that we need more scientists. Strangely enough too, we seem to make singularly little use of women in this field. As to the second factor, our lack of scientists has been widely and ably advertised. The scientist is undoubtedly the key man, the man who starts the snowball rolling but more and more, if it is to be kept rolling, gathering in speed and size we need scientific engineers and highly skilled technicians who can transform the laboratory processes of the research scientist into the practical commercial methods of industry and agriculture. I would suspect myself that their lack, the lack of these engineers and technicians is a greater drag on our progress than any shortage of actual scientists. But none of these handicaps need be more than temporary. They are not too difficult to overcome if we have the will and even with them Australia today presents an unequalled field for the progress and application of science; the continent whose resources are as yet hardly tapped, holding out such rewarding challenges as should stimulate us all.

One of these challenges is now fairly flung down in front of us. Is it too much to hope that in the immediate future there will be found among us men of boldness and imagination enough to take a leap from coal and oil to atomic power and thus place Australia far ahead in the new age. Very soon we must begin in this country, if we are to maintain our position, very soon to train the hard and practical way not only our scientists but above all our atomic engineers and technicians. Scientists today have placed in our hands power over nature, fantastically beyond any ever before used by man. Whether this is good or evil for mankind remains to be seen for the final and paramount importance of power is not how much we have but how we use it. In this the science itself cannot guide us, nor can the scientist as scientist, any more than can the man who has sold us a motor car tell us to what destination we should drive or what we should do when we get there. Science deals with material things and of necessity, and rightly, gives factual and material answers to its problems. When it comes to deciding what use we make of the power science has given us then other issues than material ones arise, first political and finally moral ones. For half a century, as the best scientific minds of our age have probed the minutest detail of matter, explored the vastest realms of space, as the frontiers of power have been pushed forward and as the horizons of knowledge have receded we have discovered that science is no longer, as it once threatened to be, at war with the things of the spirit. Knowledge and faith can support one another. The mind and soul of man can be in unity. Here in Australia, which in essence is still a pioneering land, it is vitally important that as greater and greater material powers are granted to us we should grow more and more morally fit to use them. There must be parallel advance on both fronts, but today we are concerned with the advance on one front, the scientific front and all the immense importance that means to every single soul who lives in this country. One of the most important things of that is how it should be coordinated and directed. In this Academy of Science we have a body of men who are not only qualified in knowledge, but capable with a wider wisdom to watch over that advance and here is that very important part of any command organisation, its headquarters building. In this building the oldest of the arts, architecture, has come to the service of the newest of the sciences in a happy combination of utility, originality and with a beauty that adorns our Capital and blends with our lovely countryside. It is with the greatest pleasure I now declare this building open.